Home > Resources > Our Work > State EV Policy > Freedom to Buy > Clean Fuel Standard

CLEAN FUEL STANDARD

Policy and Potential for Accelerating EV Adoption

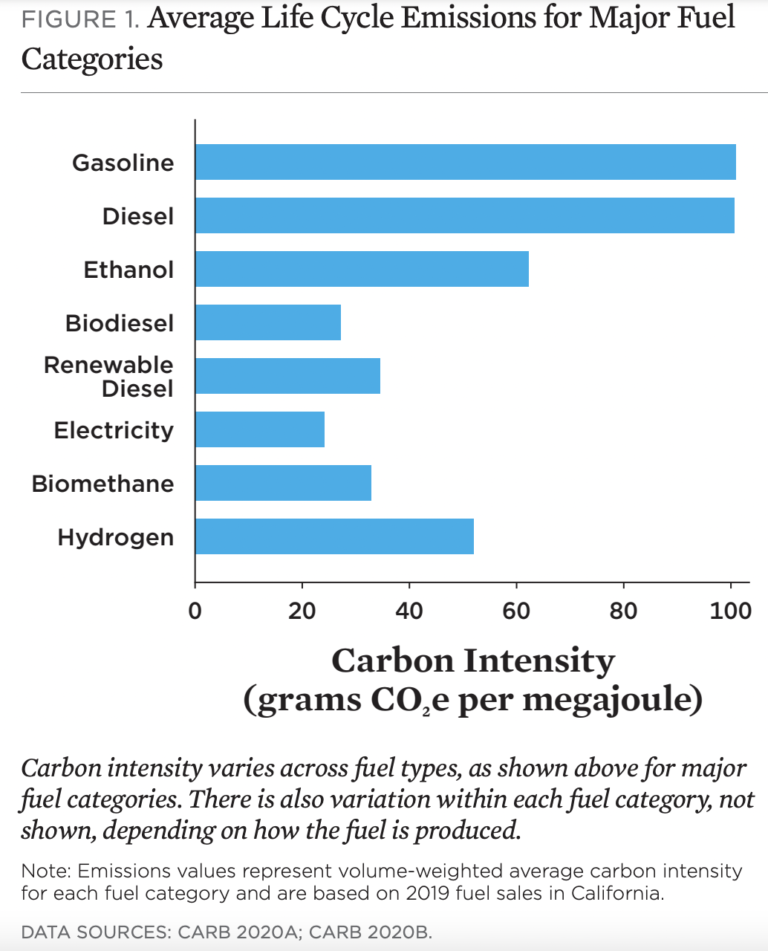

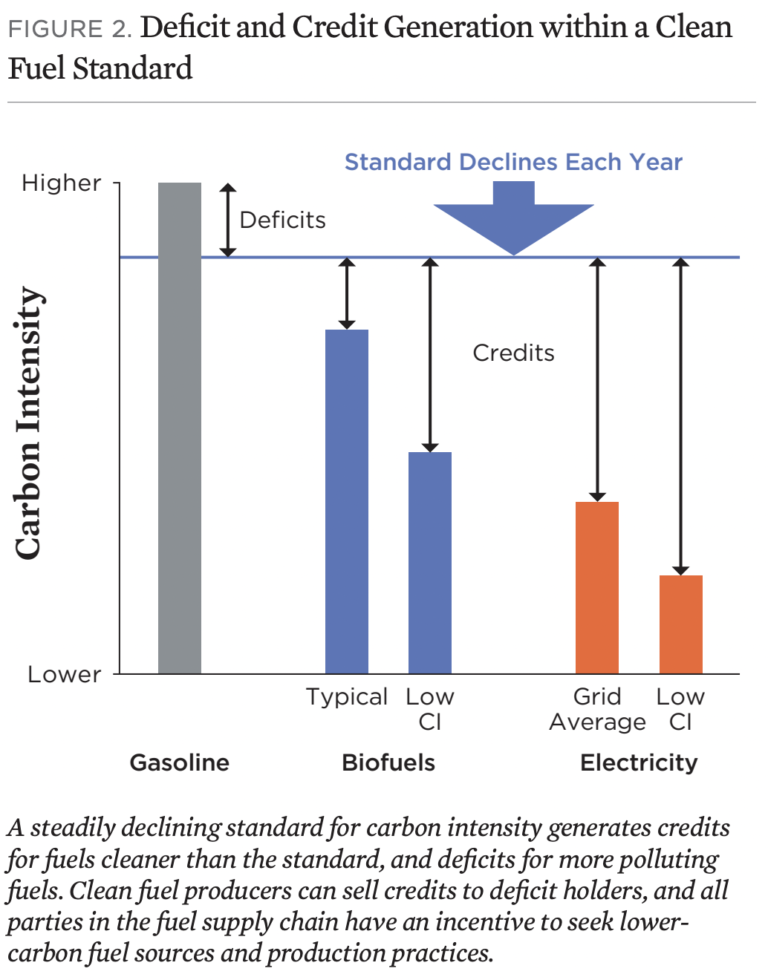

A Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) policy—also referred to as a Low Carbon Fuel Standard—sets targets for reducing the carbon intensity from fuels used in the transportation sector. A CFS policy is a fuel-agnostic performance and market-based regulation adopted by states or regions to reduce the carbon footprint in the transportation sector; diversify fuel options to increase energy security; and improve local air quality. The CFS policy sets the annual carbon intensity (CI) for all fuel providers in the transportation sector. CI measures the greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing, distributing, and consuming fuel based on a life cycle analysis. Providers below the CI generate credits, while those above produce deficits and must purchase credits to offset their higher CI. This incentivizes these providers to reduce the CI of their fuels, resulting in fuels that are cleaner.

As more of the transportation fleet transitions to being powered by electricity, a CFS policy should also include electricity as a fuel option. Since electricity receives a lower CI, electricity providers can generate a significant number of credits that can be monetized and given back to the drivers of electric vehicles (EVs), utilities, or the EV service providers (EVSPs)—or a combination thereof. Overall, this has the effect of growing the EV market and accelerating adoption.

After being introduced in California in 2007, the CFS policy has been implemented in Oregon, British Columbia, and Washington. It has also been considered in Minnesota, New Mexico, and other parts of the Midwest. The need to reduce carbon emissions in the transportation sector and improve air quality in non-attainment regions drove these states and provinces to adopt the CFS policy.

Benefits of a CFS Policy

A CFS policy has shown to be a cost-effective way to reduce GHG emissions and increase the share of low carbon fuels in the transportation sector. The policy supports the development of industries that supply low-carbon fuels, which are inherently cleaner. As electricity is included as a fuel option, the benefits to the EV sector are numerous. Additional benefits of a CFS policy include:

- Increased access to and availability of low carbon transportation fuels

- New jobs in the clean fuels sector and along the supply chain

- Investment in a diverse portfolio of cleaner fuels

- Reduced GHG emissions from the transportation sector

- Cleaner air and improved public health

- Transition of non-attainment areas to be in attainment with federal ambient air quality standards

- Increased energy independence through the production of domestic fuel sources

Impact on the EV Market

A CFS policy is a unique and vital revenue source that can supplement current EV policies and programs, such as EV purchase and charging station incentives. A CFS policy can provide a stable and long-term funding source. Most state and local funding sources for EV programs can be depleted quickly, resulting in start-stop EV programs. The CFS policy can be designed to provide credits back to the owner or operator of an EV charging station, such as a fleet operator. The revenue from selling the credits can be used to offset the current upfront cost differential between EVs and internal combustion engine vehicles as the price of EV batteries declines.

This can encourage the adoption of MHD EVs in fleets, as these vehicles would accrue more credits, given their larger batteries and higher electricity demand.

THE CREDIT SYSTEM AND EV CHARGING STATIONS

With a CFS policy, there are three ways to generate credits, depending on if the EV charging station is used for residential charging or for public, fleet, and/or workplace charging:

- Base credit: A credit generated through EV charging and is calculated with either a statewide average electric grid CI or a utility-specific electric grid CI.

- Incremental credit: A credit generated through EV charging that represents the difference between statewide or utility-specific carbon intensity and lower carbon electricity. It is used to determine the GHG impact of using electricity that is lower than the state or utility average CI.

- Capacity credits: Credits that include ZEV infrastructure crediting to support the deployment of DCFC infrastructure. These can generate credits based on their potential capacity and distributed electricity.

State Policy Design Considerations

As states look to implement a CFS policy, there are several factors that should be considered:

- Consider lessons learned: Policymakers should consider taking the lessons learned from existing CFS policies in California, Oregon, and British Columbia, as these programs have existed for over a decade and have been optimized to account for market changes.

- Include electricity as a fuel option to encourage EV adoption: The inclusion of electricity as a fuel option can provide credits back to the EV sector. This can accelerate EV adoption in the light-duty and medium- and heavy-duty sectors, including fleets. Policymakers should consider what additional policies are needed to support the EV industry.

- Include a broad coalition in the design process: As policymakers consider the design of a CFS policy, a broad coalition should be involved in the design process as many stakeholders within the transportation sectors would be impacted. Coalition partners should include transit groups, equity groups, utilities, NGOs, consumer groups, EV charging station operators, and automakers.

- Address equity concerns upfront: Policymakers must make every effort to address equity concerns upfront.

- Establish equity focused projects such as rebates and incentives available to low-income customers, electric school buses and transit buses, and other projects related to high priorities for equity-focused communities.

- Allow for flexibility with the credit design: Policymakers should allow for flexibility in determining how to distribute the credits generated from EV charging stations. Potential credit recipients may include EV consumers/fleet operators, OEMs, utilities, EVSE companies, and site hosts. A portion of credits could also be set aside to support equitable transportation electrification (e.g., funding for municipal and rural co-op utility programs, dealer programs, e-truck programs, used EV rebates, and more.) Overall, credit distribution should primarily incentivize behaviors that grow the EV market.

- Follow the science: Policymakers must consider the best available science regarding the various fuel types. The CFS is conceived as a fuel-neutral policy except concerning greenhouse gas scores, which should be assigned based on the robust analysis using the GREET model, which is in place in California and Oregon.

- Consider a regional approach: While recognizing state autonomy, states should also consider collaborating on a regional CFS approach. As a market-based mechanism, a CFS policy can have a more significant impact and achieve even greater policy objectives over a larger region. States should seek to make their CFS policies interoperable with the CFS markets in other states, both inside and outside the area.

- Set strong and long-term carbon intensity targets: To send a long-term signal to stakeholders and to create market certainty, long-term and bold carbon intensity targets should be set.

- Incorporate medium- and heavy-duty vehicle electrification: Medium- and heavy-duty EVs must also be considered in a CFS as the charging of these EVs can generate credits.

Challenges of the CFS Policy

As with any policy, various challenges must be overcome to create a program that achieves the desired market transformation and policy objectives. Challenges include:

The development of a robust lifecycle assessment: It’s essential to consider which data is included in the assessment, how the data is collected and analyzed, the correct GHG target for the state, and more. The lifecycle assessment impacts the CI of each fuel.

Designing the marketplace for selling credits: The marketplace for buying and selling credits could be a state-specific marketplace, regional marketplace, or national in scope.

Navigating fast growth in EV market: As the EV market grows, the use of electricity as fuel will continue to grow. While forecasts exist on the speed of this growth, disruptions in the supply chain could impact this growth and the use of electricity as fuel.

California, Oregon, British Columbia, & Washington

California was the first of the states to adopt this policy in 2009, with various modifications to the policy in 2013, 2016, and 2018, with its most recent updated requirements of a 20% reduction in the state fuel pool by 2030. The CFS program is currently adopted by Oregon, British Columbia, and Washington, each mirroring the version in California but reflecting differences through each market setting.

In 2018, California amended its policy to include a ZEV infrastructure credit, which was created to assist in the deployment of ZEV infrastructure, recognizing electricity as a fuel.

This credit entices more private investment for EV charging infrastructure and opens the door for more public DCFC. There is a planned statewide point-of-sale rebate program, where current EV charging credits from utilities will be pooled and given to dealers for customers to purchase EVs. This is called the clean fuels rewards program, with rebate amounts of up to $1500.

The Oregon Clean Fuels program implemented an advanced crediting program for fleets currently participating in pilot programs with a minimum requirement of one EV purchase. Credits are generated quarterly when the fleet reports the electricity used to power its vehicles. The rate of credit generation may seem a small initiative until enough credits are generated to sell them and reinvest the revenue into more EVs. Through the advanced crediting program, once a vehicle is put into service, an eligible fleet manager can request the Department of Environmental Quality issue credits up to six years in advance.

Equity and Other Considerations

A CFS makes cleaner fuels more affordable and polluting fuels more expensive. However, existing inequalities will increase if low-income people are left driving older, inefficient, and polluting cars. An equitable path to clean fuels and transportation electrification must ensure that those costs are shared fairly and that all communities benefit, especially those historically overburdened by transportation pollution. A percentage of the financial value of credits can be invested back into communities of color, low-income communities, and other communities that have been most adversely impacted by transportation pollution.

Additionally, some environmental groups may not support the inclusion of biofuels as a fuel option. However, the rationale for including it as a fuel option today could be that biofuels help to broaden support for the policy, and biofuels can serve as a bridge fuel for some vehicle applications. If designed improperly, CFS has the potential to shift efforts towards expanding the biofuels industry, especially in the near term, which would only serve to reinforce the internal combustion engine vehicle status quo and delay EV adoption. Specific provisions of a clean fuel standard can help, together with other measures that target support for electrification.

Similar Policies and Programs

Transportation Climate Initiative (TCI)

TCI is a binding cap on carbon emissions from transportation fuels in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. Participating states include Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia.

TCI requires that fuel suppliers purchase allowances auctioned by participating jurisdictions to cover the emissions from the fossil fuel components of that fuel. Proceeds from projects will be re-invested into clean transportation options and infrastructure.

No less than 50% of the annual program proceeds to go to communities overburdened by transportation pollution and underserved by the current transportation system.

Measures such as a Minimum Reserve Price, Emissions Containment Reserve, or Cost Containment Reserve, as used in TCI-P, can help achieve this goal.

A RFS (most notably at the federal level) has similar goals to a CFS, with carbon reduction strategies. Still, it is limited by excluding some fuels such as hydrogen and electricity produced from renewable sources such as wind and solar.

Certain groups are currently exploring if the federal RFS can be modified into a national CFS.

This approach limits the total amount of emissions in the transportation industry. Each source of pollution covered under the cap must hold an allowance for every ton of pollution they create. Allowances equal the total pollution allowed under that year’s cap.

Allowances are auctioned. Each regulated entity purchases allowances through auctions to cover its emissions. Proceeds can fund programs to further reduce emissions or provide other benefits to households and communities.