Guest post: Paul Ruiz, Senior Policy Analyst, Electrification Coalition, Twitter: @pmruiz.

Original article published on The Fuse, January 15, 2019.

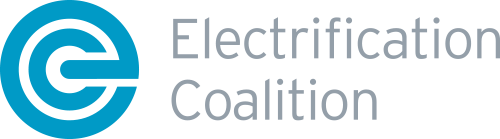

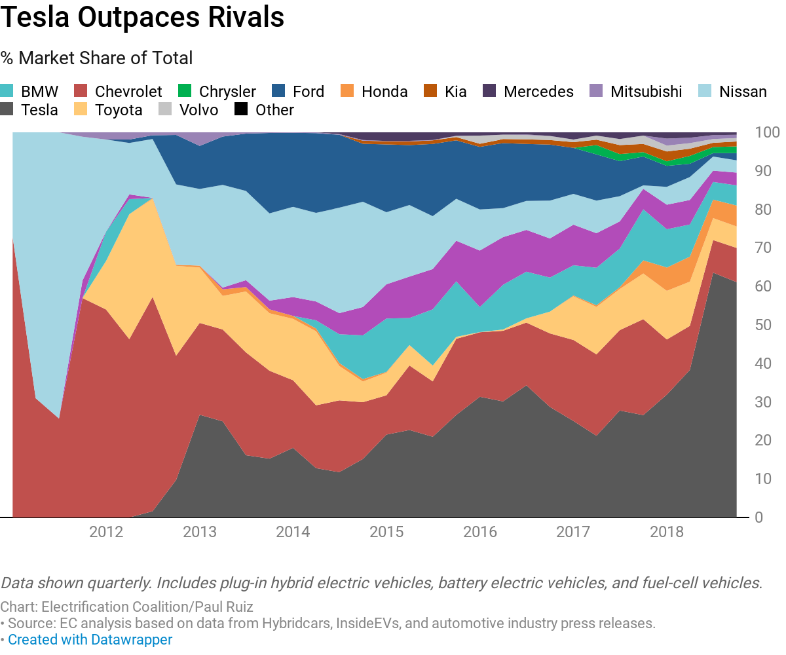

Electric vehicle (EV) sales in the United States grew impressively in 2018. National data for the full 12 months ending in December show automakers sold more than 362,000 units, an 83 percent increase over 2017. This exceptional rate of growth was largely driven by one automaker, Tesla, which significantly ramped up its production capabilities in the third quarter and completed deliveries on its mass-market Model 3 sedan. More than half of all EV sales in 2018 were Teslas (52 percent) with the Model 3 capturing more than 38 percent of sales alone.

More than any other currently available battery electric vehicle (BEV), the Model 3’s success shows there is tremendous pent-up demand for more affordable all-electric cars. Consumers also demand choice, as evidenced by the growing number of models currently available in the national market and automaker announcements of new MY 2019 and 2020 rollouts. This year and next, automakers will release at least a dozen new BEVs and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and a growing share of those additions will fulfill popular consumer interests, such as sports cars and sports-utility vehicles. There are now more than 16 BEV models available to consumers nationwide and 29 PHEVs. As battery costs continue to decline, analysts project a growing number of these cars will go further on a single charge and at a lower cost.

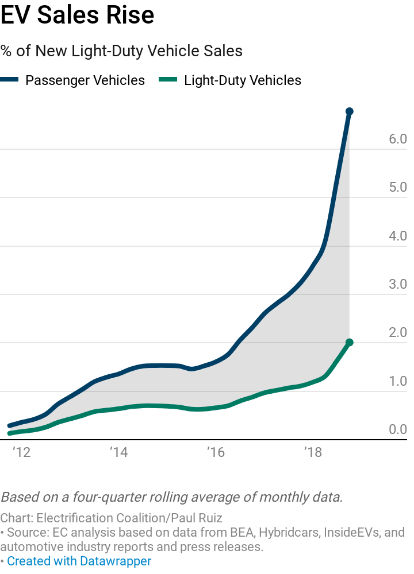

These are encouraging signs, but there are reasons to temper our expectations in 2019. EVs currently represent just one out of every 50 new vehicles sold in the United States—undoubtedly better than the nascent market of only a few years ago but still a niche within a car market that sold more than 17.4 million units last year. According to the latest data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and InsideEVs, the combined category for BEVs and PHEVs accounted for just above two percent of new vehicle sales in the United States. Much of that growth has been concentrated in states with robust zero emissions vehicle (ZEV) programs and driven by a federal $7,500 tax credit available to OEMs’ first 200,000 vehicle sales. In late 2018, GM hit the 200,000-vehicle mark, triggering a phaseout of the popular tax credit on the OEM’s vehicle sales. Tesla has similarly hit the cap. In both cases, prospective buyers will now only be eligible for a tax credit of up to $3,750 through at least the first six months of 2019.

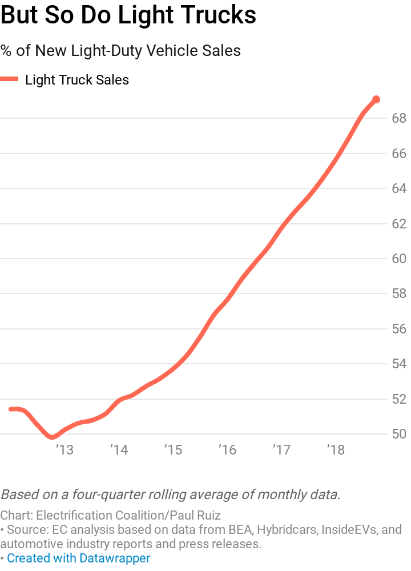

It is also important to note that while automakers are introducing new models, some will be offered only in limited quantities in a few U.S. states. Mercedes, Porsche, and BMW have all announced new model year vehicles that fit this description. The high-end Mercedes EQC, for example, will be produced in large quantities in Europe, but offered at significantly lower volumes in the United States. Mercedes—like many popular brands—is still developing plans to mass-market EVs in the U.S. Complicating that strategy is U.S. consumers’ decisive shift away from smaller sedans and toward larger pick-up trucks and sport-utility vehicles (SUVs). On an annualized basis, light trucks represent nearly seven out of every 10 new vehicles sold in the United States, an unparalleled figure that does not show signs of slowing. “It’s Plug-ins Versus Pickups in the Newest Culture Crash,” read the headline for an article on EVs by Bloomberg Opinion over the weekend. Several automakers plan to introduce electric SUVs and crossovers in the next several years, joining the Tesla Model X, Jaguar i-Pace, and the Hyundai Kona EV that are on the market in 2019.

Nearing Inflection?

The U.S. EV market will undoubtedly achieve many milestones over the next five to 10 years. But rather than focus on individual markers, let’s think about the big picture. When will be the point of inflection? When will the adoption curve rapidly transform U.S. transportation? There are positive signs that suggest the U.S. is trending in the right direction. In October 2018, the U.S. EV market hit 1 million cumulative sales over 2011 levels, with cumulative sales reaching more than 1.1 million vehicles by year’s end. Nearly every traditional automaker has announced medium- to long-term plans to electrify its light-duty vehicle fleet. And, importantly, at the end of 2018 there are more than 60,000 public and private EV charging outlets in the U.S.

But these signs by themselves do not mean the inflection point is near. Last May, the International Energy Agency said global EV sales will triple to 13 million by 2030, provided the world builds at least 10 gigafactories to produce batteries at scale. Given the improved efficiency and durability of U.S. light-duty vehicles and the slow turnover in the U.S. vehicle fleet, internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) will be around for quite some time. To reach lift-off in EV sales figures—to the point of majority versus ICEVs—dedicated government policy alongside private sector R&D will be necessary to continue encouraging EV adoption, IEA says. In the U.S., this means lifting the cap on the federal EV tax credit, advancing more state and municipal policies that increase adoption locally, encouraging consumers to test drive EVs, and building out the infrastructure to support this vibrant ecosystem.

2018 was a great year for EVs, but oil is still the dominant transportation fuel that almost exclusively powers the way Americans move. We cannot let enthusiasm for the recent sales obscure the much larger policy and consumer commitment it will take to overcome oil’s monopoly on the U.S. transportation sector.